"Not TV or illegal drugs but the automobile has been the chief destroyer of American communities," wrote Jane Jacobs back in 2004, pointing out that the vast majority of street design decisions in North America revolved around automobiles rather than people. The goal was twofold: to move the maximum number of vehicles through as quickly as possible, especially at peak time, and to provide drivers with enough space to park their vehicles. By allowing huge amounts of land to be dedicated to parking, for decades, North American policymakers shaped not only the American urban landscape, but also citizens' understanding of how streets should work and look like. Among other things, we accepted the fact that acres of asphalt sit empty for most of the day. But that is beginning to change.

For the last 50 years, automobile-centered urban planning has made poor use of valuable land and a poor return on what is ultimately a public investment. How? According to the Victoria Transport Policy Institute (VTPI, 2013b), most of today's North American cities have three to six parking spaces per vehicle. Another study analyzing 27 mixed-use districts in the United States concluded that on average, parking supply exceeded demand by 65 percent (Citylab, 2014).

In addition to building more parking space than is actually needed, policy makers built exorbitantly wide and expensive roads. Research shows that North American street design was and is dictated almost exclusively according to performance indicators based on the speed of vehicular flow. This has resulted in over-built and extremely wide streets designed to maximize traffic flow and supposedly reduce the chances of collision.

With this in mind, Slow Streets sought to determine the most collision-prone streets in Vancouver. Against the argument supported for decades by policymakers, we found that indeed, road lane width was positively correlated with higher rates of collisions between vehicles and people walking and cycling. Wider roads make drivers feel safe when traveling at unsafe speeds and also make them more forgiving of driving errors. Using 2009-2013 automobile insurance data from Insurance Corporation of British Columbia (ICBC), we found that on average there were 1.490 vehicle collisions involving people walking and cycling at intersections with two lanes of traffic. When looking at intersections with six lanes of traffic, the average number of collisions more than doubled (3.412). In other words, 3.5 people got hit by a car on a six-lane road vs. 1.5 people on a two-lane road.

Designing streets with the sole purpose of pushing through as many vehicles as possible not only endangers human lives, but also erodes some of our most critical assets: public space and community-building. In terms of value, this design approach contributes little to the overall community other than moving traffic through quickly.

At Slow Streets, it is our objective to connect streets—15 percent of the public space available in our cities (Next City, 2015)—to broader values. We believe that cities can generate more value and a greater return on investments by simply designing our streets for "slower" modes like walking and cycling.

Rethinking Streets

East Vancouver's Commercial Drive is the prototypical example of car-centered street design. With six lanes of vehicular traffic, Commercial Drive is treated primarily as a thoroughfare for automobiles, whose size and speed create an uncomfortable walking and cycling experience. This streetscape design fails to reflect the neighborhood's importance as one of Vancouver's most cherished streets for shopping, culture, and dining. To support this idea, we sought to provide data on the type of activities occurring at the street level.

Between September and October 2014 we observed over 1,000 individuals on weekday and weekend afternoons as well as on peak evenings. We focused on observing the type of activities they got involved in, and also on how they travelled to our study site.

We observed that 93 percent of people arrived at our sample study sites on foot, while only 2 percent did it by car. When compared with overall vehicular traffic, a clearer picture emerges. On average, 916 vehicles pass through Commercial Drive per hour (Van Map, 2013). If we assume that a vehicle is carrying on average 1.27 passengers (Translink, 2011a) then Commercial Drive dedicates more than double the street-width to move people driving as opposed to walking.

In terms of parking, during peak hours we found that average occupancy rates were 82 percent, suggesting that parking is over-supplied.

We also observed that only 14 percent of people walking on Commercial Drive socialized there. Instead, they often stood on the side streets, away from traffic and adjacent to buildings. We found that traffic noise could be the reason behind this low percentage of "schmoozers" on Commercial Drive itself, since, according to our measurements, traffic on Commercial Drive generates 76dB of noise, the equivalent of standing 15 meters away from a highway.

The Importance of Traffic Calming

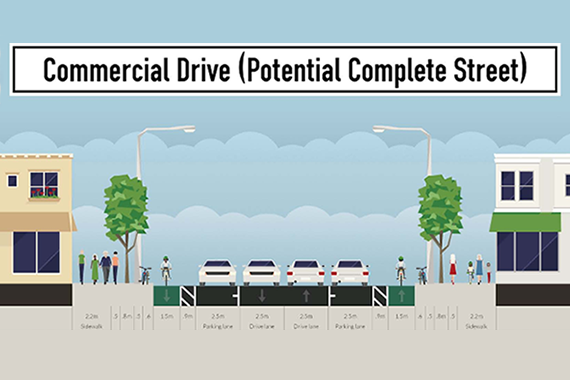

To reduce the negative impact of automobile traffic on Commercial Drive, we suggested an alternative street design known as a Complete Street. Complete Streets allow people to travel comfortably and safely regardless of their mode, age, gender, or ability. A Complete Street also acknowledges the importance of people walking and cycling, by giving them more space.

Located in the same city, Union Street serves as an interesting example of a well-executed Complete Street, and is a useful comparison as it features a similar mix of commercial and residential uses to Commercial Drive.

Union Street on a typical day. 1) Vehicles protect cyclists 2) Buffer zone protects drivers from cyclists and cyclists from being "doored".

Despite their similar mix of retail and commercial activities, Union Street and Commercial Drive are quite different in terms of street design. Commercial Drive features six lanes of vehicular traffic, whereas Union Street features only two. As a Complete Street, Union Street features a separated bike lane which is buffered by vehicle parking (see images above) and wider sidewalks, while still maintaining automobile access. This design produces a much more people-friendly environment—traffic generates only 70dB of noise (the equivalent of a radio playing). Union Street demonstrates that it's possible to increase the capacity to move more people in the same amount of space while maintaining access for all modes of traffic. Union Street has four times the cycling traffic (289 per hour vs. 65 per hour) and one-fifth less vehicular traffic when compared with Commercial Drive and still supports similar numbers of people shopping (12 percent vs. 14 percent). This demonstrates that less room for vehicles doesn't imply less people shopping.

Looking at it from a business perspective, Slow Streets found that 71 percent of business owners thought that having a separated bike lane was good for Union Street and in 57 percent of the cases, also for their businesses.

Existing studies across North America confirm our findings and the need for slower streets. One of them observed five American cities and over 10,000 cyclists, and found that approximately 20 percent of them stated that the frequency which they stopped at shops increased after the installation of the protected bike lanes (NITC 2014).

The pedestrian experience of Union Street, although difficult to quantify, is also much more pleasant when compared with Commercial Drive, as walkers are protected from vehicular traffic by the bike lane and parking lane.

People are What Generate Value for our Cities—not Cars

Streets offer a platform for creating social, economic, and environmental value. They are the vital arteries of our cities. While our comparative study is Vancouver-specific, its teachings are applicable to all cities in North America.

First, walking, and cycling infrastructure is extremely inexpensive to build when compared with vehicular infrastructure. In terms of construction costs per meter, roads cost $752,480 per meter, which is more than three times the cost to provide the same amount of protected bike lanes ($213,485 per meter) and sidewalks ($167,466 per meter) (VTPI, 2013a). (All these figures are in USD).

Second, research consistently indicates that when you build active transportation infrastructure, people will use it. Since 2008, Vancouver has implemented a number of separated bike lanes throughout the city. As a result, from 2008 to 2011 alone, trips by bike increased by a full 40 percent. Moreover, more people are willing to cycle if adequate, comfortable, and safe cycling infrastructure is provided. As many as 41 percent of people in Metro Vancouver don't cycle more because they feel unsafe mixing with high speed traffic (TransLink, 2011b). Certainly, walking and cycling are more environmentally friendly than driving. If we want people to travel by these slower modes, we need to provide safe and accessible infrastructure.

Finally, humans are social by nature. We are happiest when we are around other people. As the saying goes, cars, on the other hand, are happiest when no one is around.

There are positive signs that a change is taking place. Montreal recently outlined a plan to pedestrianize five streets this summer. New York City had great success in making Broadway and Times Square more people-friendly. In Europe, a number of cities are working towards being car-free altogether. The evidence is mounting that we can facilitate healthier, wealthier, and more sustainable cities through more appropriate designs and allocations of our public streets so they reflect the way human beings—and not cars—use them. We just need to . . . slow down.