Dallaire recalls the agony of not being able to take action to halt the Rwandan genocide because he lacked the requisite authority as well as manpower and equipment. In essence, he lacked the support of the international community.

JOANNE MYERS: Good morning. On behalf of the Carnegie Council I would like to welcome our members and guests to a very special morning.

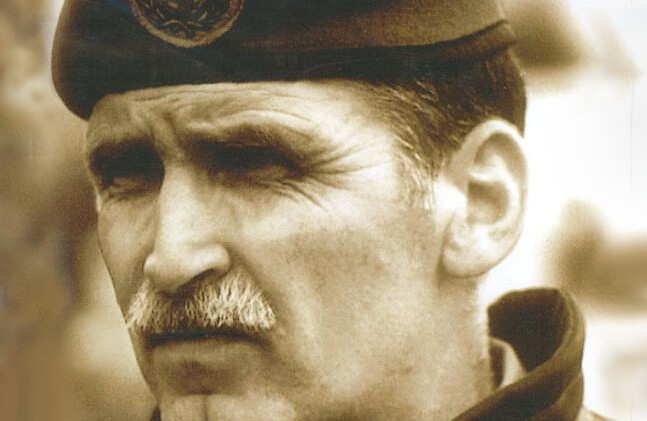

To me it is no surprise that so many of you would turn out to welcome a man who was so caring during the darkest days of the Rwandan genocide. The person I am speaking about, of course, is General Roméo Dallaire, who really embodies what the Carnegie Council stands for: ethics in international affairs.

For today's program I have asked the Canadian Ambassador to the United Nations, Paul Heinbecker, to introduce his heroic countryman, for as Ambassador Heinbecker once told me, General Dallaire is one individual that he personally has enormous admiration and respect for.

Ambassador Heinbecker joined the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade almost forty years ago. He began his career at the Canadian Embassy in Washington, and since that time he has held a variety of interesting and important positions, including Chief Foreign Policy Advisor and speech writer to the Prime Minister, Assistant Secretary to the Cabinet for Foreign and Defense Policy, Assistant Deputy Minister for International Security Affairs and Global Issues, and Canadian Ambassador to Germany.

Ambassador Heinbecker, the floor is yours.

AMBASSADOR HEINBECKER: Good morning. General Dallaire is a Canadian hero. He served in the Canadian Army for thirty years. He is a graduate of the Collège Militaire Royal. He has commanded an artillery regiment, a brigade group, the Collège Militaire Royal itself, the First Canadian Division.

What we know him for is his experience with the United Nations, and particularly in Rwanda. He has, since his retirement in the year 2000, been a Special Advisor to the Minister of the Canadian International Development Agency [CIDA] on Children and Armed Conflict, and he is also Special Advisor to the Minister of Defense on Educational Reform in the Canadian Forces. He has won the Meritorious Service Cross, the Vimy Award, and the Legion of Merit from the United States.

In January 1994, General Dallaire sent out the alarm with credible information of an impending catastrophe. The United Nations and the membership of the Security Council failed General Dallaire, it failed the people of Rwanda, and it failed humanity. “Never again” was what we had all said. General Dallaire told us that “never again” was happening again, and the Security Council played word games with the Genocide Treaty. It was one of the darker moments of history.

Secretary General Kofi Annan, on behalf of the Secretariat, took responsibility for their part of this failure. But it took the countries of the Security Council, particularly the Permanent Members of the Security Council until April 2000 before they had a public discussion of what happened in Rwanda and made their own gestures of regret for what had happened.

General Dallaire is here to talk to you today about his experiences and about “never again.” Please join me in welcoming this extraordinary speaker.

RemarksGEN. DALLAIRE: Thank you.

Rwanda is a paradise of hills and of valleys, of the eternal spring, but also the memories of a very dark cloud, of a smog of death, that enveloped that country now nearly ten years ago.

I would like to speak of that, but also try to move it to another plateau – the whole arena of conflict, of ethical and moral decisions, of humanity, the arena in which one could sit back and ponder the following question: are all humans human, or are some more human than others?

When one looks back at Rwanda or now at the Congo – still on and still the terrible pestilence and destruction of human life – our enormous concentration on Iraq, we want to ponder that question: are all humans human, or are some more human than others?

In January 1994, warnings were sent out with the information that we wanted to take offensive action against the extremists who had weapons that ultimately we were sure were to be used against us, or against the Rwandans if the situation fell into catastrophic failure.

Nine years ago in January, I was sending the third message in that regard, saying: We have an insight into the extremist organization. We are capable of milking this individual since he can help us wrest the initiative from the extremists and permit the moderates to move forward—and move with the moderates, not in a subversive fashion, but at least in an assistance fashion—with demobilization, reintegration of the different forces, and the bureaucracies to build a nation in a peaceful fashion.

That third cable got a similar response to the previous cables, but it had a particularly sad connotation to it. The informant, now having fed us significant information at enormous risks—and we were able to confirm that information, because I had a couple of my Franco-African officers in civvies go into some of the sites and find the weapons and who owned the buildings—told us that he was running out of capability, that is, he was ready to give us everything we wanted, or as much as he could, but he would have to leave. His concern for his family was enormous. He had three children, a wife. He wanted a guarantee that he could escape once he fed us this information, and probably continue to feed information from outside the country. All he wanted was $5,000, a couple of tickets, and a country somewhere to take him in.

No one took him in. The United Nations and the processes that we were involved with, Department of Peacekeeping Operations [DPKO] did not have the authority to move a person out of a country and provide him exile protection.

France, the U.K., the U.S., Belgium, Germany were directly requested. I went personally to try with the ambassadors to find a few dollars and a willingness to move this person, even temporarily, into their countries so that we could get the essence of the structure of the extremists to throw them off kilter, to take the initiative, and move, not necessarily the political process that had stagnated by then, but the military process through the Joint Military Committee and with the moderates undermine the extremists’ power base. It didn’t happen.

Two more messages were sent, and ultimately he disappeared. We never knew or will never know what happened to Jean-Pierre.

That is one example of a number of quandaries, ambiguities, and certainly a number of ethical and moral decisions that were taken not just during the genocide but up to the genocide. The bulk of the book that I am writing leads you to the genocide and all the peregrinations, the different interactions between the international community, between DPKO and the Department of Political Affairs [DPA], with also the Department of Humanitarian Affairs, the Secretariat, the Secretary General, the Secretary General of the OAU—all the different players, all the different opportunities which were lost by process, lost by mandated complexity, lost by inflexibility of decision-making and interpretation, but, worst of all, lost by the apathy of the same international community that makes up the U.N.

There was no lack of information. All the major players had ambassadors, military attachés. They knew, intelligence-wise, very well certainly most of the dimensions of what was about to happen. There was no transfer of information whatsoever, none. Nothing was transferred to the U.N. before, during, and certainly after, to my military force or to the mission in order to assist us in preventing genocide—or even during the genocide, being able to adjust whatever force I had at the time to help those who were in danger, help the humanitarian effort that was going on throughout the country.

One country was prepared to sell me satellite photographs so that I could find out where the bulk of the displaced people were—50,000 people are fairly easy to find—where they camped so we could move the humanitarian aid to help them. It wasn’t in the budget. I couldn’t find the money to buy those satellite photographs, even as I saw electronic warfare aircraft from Western powers, NATO powers, flying overhead.

The ethical dilemmas in which we find ourselves in conflict resolution go far beyond where we found ourselves in classic warfare during the Second World War, even in Korea, or Vietnam. Since the fall of the Wall and the end of the Cold War, we have entered an era that is revolutionary, where classic warfare, with known enemies, with all the instruments, all the sophistication, is passé.

We had the surge of the Gulf War, where we used all of our instruments, proved all the doctrine and training that we had for fifty years in NATO, and we went at it, and it all worked, and we were very happy. That we were fighting a First World War enemy was irrelevant, of course.

From there we continued to move in an era of imploding nations, of complexity, of mandates, and of ad hoc’ery, even on-the-job training by many of us, in attempting not to solve the crises, but to try to get ahead of them, to prevent them, and once in them bring innovative solutions. And I speak not only military—I speak diplomatic, I speak humanitarian. I speak of methodologies that we developed during the Cold War that we have been trying to adapt to respond to these very complex situations in which simple solutions simply won’t meet the requirement.

It is the new era of conflict resolution that brings about not only complex solutions but also long-term commitment. We’re into conflict resolution in these countries for ten, twenty, thirty, forty years, not two years. Rapid mandates, where I have to bring a very difficultly-built peace agreement to a democratic process in two years in which 85 percent of the country was of one ethnicity. The pressure of that prevented much initiative, many ideas to flow, much thinking, and many new ways of conciliation. It prevented that to happen and kept compressing those caught up in the maelstrom of, not only the extremists trying to undermine the process, but even the moderates and the outside community in trying to provide solutions that would move them down that road.

They’re in it for ten, twenty, thirty years. But you’re in it in a new way. Gone should be the era of a military, humanitarian, diplomatic, political or nation-building plan. There is no positive solution with building parallel integrating plans.

What is required of this era are multi-disciplined leaders, workers, thinkers, in order to marry these different dimensions and to operate in one plan that at times has more military or more security than diplomacy, and at other times has more diplomatic—to be able to maneuver all these different dimensions not in reaction but, nearly instinctively, to move the yardsticks versus reacting to the yardsticks. We’re in conflict resolution. We are not in war. We’re into a whole new dimension of flexibility of instruments, but we also need a new dimension or arena of skills.

We don’t even know the real verbs to be able to operate in these new conflict arenas. It became easy, in the Cold War. NATO had its lexicon. And militaries operate with action verbs—defend, attack, withdraw. Everybody knew what it meant.

What does “establish an atmosphere of security” mean, which was my mission? Does it mean that I defend Rwanda while they’re demobilizing from an opportunistic neighbor? Does it mean I watch? How far do I go? How much force do I use? What are my rules of engagement? How much can I defend the process? How much can I protect civilians under a Chapter Six mandate?

We are in an era where it’s no more simple action verbs. It’s an era where you need more intellectual rigueur, more depth. Médecins Sans Frontières is leading the way in saying, “No, you don’t go in and help because people are hurting; you look at the situation and go in and help.”

In Rwanda, the bulk of the humanitarian aid went to Goma [Democratic Republic of Congo] in the north and into the northeast behind the rebel lines, and they were helping 5,000-6,000 people at different hills. The Rwandan Patriotic Forces [RPF] were taking their cut of the fuel, food, and water and medical supplies. There is something unethical about discussing, about going into a debate on, how much of the aid you should give to the people in charge of that arena in order to provide some to other people. There is something fundamentally unethical about this methodology that has crept in our ways of operating and the humanitarian efforts.

The era of isolation between us is no more. How do we integrate those capabilities and how do we bring them about?

The skill sets of this era are intellectual. They’re not tactical, they’re not doctrinal, they’re not process. They’re based on anthropology, sociology, philosophy, and on trying to understand the nuances that are in play—and try not to simply witness, as we had to, to fall back, because we couldn’t use force—but they’re built on the ability to proactively function in ambiguity.

Now, imagine the military operating in that context. It is a revolution. It is a whole new set of skill sets in order not to use the force, but in fact keep that in an over-watch, but be instruments integrated with the political, diplomatic and humanitarian in order to advance in the long term a change—not a revolution, a change.

Change takes time. Change means that you will work at all levels, including grassroots levels. It means that yes, you’re going to demobilize child soldiers, but you’re going to educate them, give them an opportunity. And it will take a couple of generations before they are able to discuss, defend, argue, make their own decisions.

A Conference of the Americas was held a couple of years ago in Quebec. The Youth of the Americas also met for a week. I attended that meeting representing CIDA’s Minister. On the final day of the symposium when they presented their final report, do you know what all of them said? For the future of the Americas, they all said that they want more education. They want to be able to have the ability to decide, to understand, to shift.

Currently we’re involved with this new dimension of conflict, which is the use of children. It’s new because it has become more and more efficient. It is used also in even organized crime, with eleven-, twelve-, thirteen-year-olds involved in drug trade. Children are replacing adults because the weapons are so light and easy to operate. Children are expendable. And children create enormous quandaries in those who face them.

There is a young sergeant with a dozen or so soldiers who was able to move into a village after negotiating through various roadblocks. The village had been wiped out. There were people who had hidden in the surrounding banana plantations. When they saw the soldiers arrive, they came out and congregated around one of the few churches that had not become a slaughterhouse, because that also is part of the exercise. They don’t play by any rules—none.

We have a great desire to imitate Marlon Brando in “Apocalypse Now,” the seminal Vietnam War movie: Duval, with all the toys and blowing away people and to hell with the Geneva Convention; and then Marlon Brando going ethnic and becoming more ruthless than the enemy.

And so they destroy their own. The people in many of these missions were slaughtered because that’s part of the exercise of gaining and maintaining power in those countries by the rebels or the governments.

The sergeant is there with a couple of hundred people congregating. He calls back to the headquarters to get transport to pull them out of there into safe sites—not safe zones, as my military colleagues prevented me from implementing. They wanted me to implement a safe zone during the genocide—take southern Rwanda, put a wall across, and the Tutsis can be safe inside there. The Tutsis couldn’t make it there because there was a roadblock every 100 meters.

Suddenly, from one side of the village comes a group of young boys, twelve, thirteen, fourteen, and they’re shooting at him and the people he is defending. And from the other side there is a group of girls coming, and behind them are boys shooting at the sergeant, at his troops, but, most importantly, at the people they’re supposed to be protecting.

What does the sergeant do? Do you kill children? This is one example of the moral and ethical dilemmas in which we find ourselves in many of these conflicts. They’re not high-tech, but they require a depth of intellectual rigueur, they require values and people who know to go beyond themselves and potentially sacrifice themselves—not because the order or mandate is there, but because morally and ethically that’s the right thing to do.

The sergeant opened up fire and took casualties. He killed children. Is that the solution? Is that how conflict is going to be resolved? Do we move to another level of inhumanity, create a higher plain of human rights, a higher plain of the respect of the individual, a higher plain of humanity?

Ladies and gentlemen, we’re very concerned about Iraq. How many people have been talking about the slaughter in the Congo?

Thank you very much.

JOANNE MYERS: Thank you. I’d like to open the floor to questions

Question & AnswerQUESTION: You twice mentioned the Congo. Do you see a difference in the way we are facing the Congo today compared to Rwanda?

GEN. DALLAIRE: It began in subsequent situations – Sierra Leone, for example,—where either ex-colonial powers, mostly with a sense of responsibility, which I applaud, go in to assist in re-establishing security in those nations.

I do not applaud how much is being done outside of the U.N. I can’t fathom why single-nation-led coalitions are the solution for the future. There’s no body internationally that is more transparent and impartial than the U.N.

A single-nation-led coalition has an ulterior motive. If it’s human rights, tant mieux. But is it? So much is self-interest.

And so this movement away from the U.N., away from Brahimi’s [Brahimi Executive Report] reforms, to go with national capabilities, avoiding command and control, avoiding mandates of the U.N., getting tacit agreement, to me is a regression. It is not a positive move for the future.

You get some instantaneous results, but you’ll get it in places where people want to go, not necessarily where people should be going or have to be going.

QUESTION: I wonder if the rhetorical question that you posed just now isn’t the point. Some human beings are different from others because they have the misfortune to live in countries which do not attract the same degree of international attention, and it is a fact of life that results from the inability to match resources to the demands that you’re posing. Neither the international community nor the leading members of the United Nations have unlimited financial, military, or moral resources to tackle every single problem.

That means, therefore, that in realpolitik there are only some countries that are prepared to make the effort. If you have a disaster in the South Pacific, we all look to the Aussies to go and sort it out. If you have a disaster in Francophone Africa, there’s nobody else but the French who are prepared to put their money where their mouth is and go and sort it out.

With great respect, there is no British self-interest whatsoever in Sierra Leone, but we felt a moral compunction to go and help sort it out.

The problems with Rwanda were precisely that, that there were only two countries in the world that took Rwanda seriously, the Belgians and the French. You talked about the lack of intelligence. We, the British, a member of the P5, had no mission in Kigali [Rwanda] or Bujumbura [Burundi]. The only intelligence we had on what was going on in Rwanda came via the French, who were constantly nagging us to do something about the RPF, most certainly. But we had no intelligence, nor did we have any national interest whatsoever in the lead-up to the genocide.

You must recognize, therefore, that some humans are different from others because they have the misfortune to live in countries, like the Congo, which, regrettably, simply do not attract the same degree of emotional or national interest of those who can do something about it.

GEN. DALLAIRE: Yes, I totally agree. You argue very well the situation of realpolitik. That’s why 800,000 can be slaughtered in 100 days in Rwanda and nobody gives a damn, in fact pull out, and we’re pouring billions and still have over 10,000 troops in Yugoslavia. There were more people killed, injured, displaced internally, and made refugees in 100 days in Rwanda than the whole of the Yugoslavian campaign. But the Yugoslavs are white, they’re European, they’re friends, they were allies during the Second World War—they count.

Eight hundred thousand Rwandans don’t count. The question is: why don’t they count? Why do we continue with that sort of premise that they don’t count as much?

I applaud the altruism of the U.K. in Sierra Leone. I would suspect that there was a sense of past colonial responsibility, or something of that nature.

But it makes no sense to humanity that 80 percent of it will stay in the mud, 80 percent of it will still eat the handouts of the 20 percent. We are like many countries. The residual of any of our budgets, if there is a residual, will go to aid. It is not a primary focus. It’s not a mainstream activity.

There was a senior officer from a large Western power who probably responds very much to what you have been saying, and which is the reality. I am maybe a bit unrealistic in that way because I am not looking at today and tomorrow; I’m looking twenty, thirty, a hundred, two hundred, years from now. I’m thinking of what Kofi Annan said in his seminal speech at the General Assembly at the Millennium in September 2000, “We the peoples.” This is the millennium of humanity; this is not the millennium of technology.

To me, humanity is 100 percent. The aim is to move towards that. The aim is to move from the self-interest level to the humanity level.

I believe that there are capabilities within the U.N. to be exploited in order to advance us that way. As an example, why would the United States in many cases say that it is the world policeman? That is not the role of the United States. It is the world power, and internationally with its force it should be the world power, not the policeman.

In my country, if you have an insurrection, you send in the police to sort it out. If it doesn’t work, the army goes in, and they will ultimately be held accountable because there’s nothing else behind the army. They have to win.

In this era of conflict, in many of the zones, we could send in middle powers, we can send in nations that have achieved a certain level of development in human rights and the ability to conduct operations under the premise of the Charter, and have the larger nations in over-watch, keep the political will behind the effort of the middle powers. If we find ourselves into catastrophic failure, then the world power, with its might, can come in and re-establish the situation.

The way of the future in many of these conflicts is the ability of middle powers to take on more of the responsibility in many of the conflict zones under the U.N. auspices.

QUESTION: One of the biggest problems is that there are many countries without any superpower interest.

Coming to a situation that Kishore Mabubani talks about occasionally, perhaps not quite so long ago, the Security Council sent a mission to central Africa. Lots of ambassadors went, and they focused very briefly on Burundi. When they got back, they all agreed that it was a powder keg, that genocide was perfectly conceivable in Burundi in the near future. There was an understanding that none of the five Permanent Members were likely to want to intervene if genocide broke out in Burundi. There was no contingency planning, and no desire or willingness to any commitment.

So the big problem is the orphan countries that have no great power interest whatsoever. It would be nice to think that the middle powers will be intervening in years ahead in these situations. Indeed, for Burundi, South Africa has become a sort of godparent by default and is taking significant military and political risks there.

But one thing that alarms me in the West is that the militaries of the middle powers in the West now just want to play with the big boys. They don’t want to go into Africa and take risks on their own. They principally prefer to go along with the British, the French or any other of the major powers willing to deploy.

In the recent past, I’ve seen in my own country, Canada, a withdrawal of the military from a willingness to go off to dangerous places and take risks. Part of that was our experience in Somalia or indeed the experience of Rwanda, where Canada also failed to reinforce General Dallaire, failed to do the right thing. Canadian politicians have taken no responsibility for that whatsoever. We can break this pattern of middle power military simply wanting to play in the big leagues.

GEN. DALLAIRE: The point I was going to make earlier on is that instead of recommending sending troops to Rwanda, a nations’s officer came to me and said they wouldn’t send them because there was no strategic interest, no strategic resources. And, in fact, they said, “The only thing that’s here are humans.”

Since the treaty of Westphalia, militaries have defended nations and, yes, their interests abroad. However, that is no longer enough. In nations like the one I come from, middle powers, being a war fighter is not enough. While you do need military skills to operate in conflict, you also need conflict resolution skills. We need to learn to strike a better balance between the two. None of the militaries of the Western world, however, are keen on doing that because you move away from classic warfare and into an intellectual realm.

Weapons systems are essential to fight a war fighting entity, but the question is: Is that your mainstream activity, or is that only one of the skill sets that you need? Ninety-five percent of our militaries’ time is spent on training for classic or adapted warfare situations in places outside of Europe. But we have been employed 95% of the time in conflict resolution, in places where many of those weapons systems have no use. And we’ve been taking casualties.

QUESTION: I am puzzled for a moment with the distinction you make between classic and modern, and what you call ambiguous, warfare. In the latter case, you mention Afghanistan with the CIA throwing money around, paratroopers, proxy armies, etc. To me, this seems to be classic warfare. This is how we have always won wars when we win them, and probably how we have always lost wars when we lose them. It has been a long time since we had two cavalries riding across an open field towards each other and that warfare. There is always a mixture of straightforward, classic warfare and a lot of sloppy stuff. One of the problems with going through the United Nations is that countries don’t like doing the sloppy stuff. The UN is good only when there are two lines, when there is a truce, and when you can put in peacekeepers. Can the UN do non-classic warfare?

Also, you talked about the orphaned parts of the world where the major powers have no interest. I wonder if part of the problem is that we present these cases as humanitarian problems, where both sides are called crazy and they have comic book names like Hutu and Tutsi. But there is never any talk about them being political problems, which is how we described Afghanistan and also Bosnia, where we have something at stake. Would it be more effective to describe these situations as political problems? Does this humanitarianism approach undermine itself?

GEN. DALLAIRE: In Rwanda, for nine months, there was a massive political exercise with moderates, extremists, rebels, and others to bring about a political solution. But no one was interested; diplomats simply reported the news to their superiors. There was also no real intellectual effort the other way to understand the situation and bring about peaceful compromise. The military was there purely as an instrument to stop the warring factions. The political effort never came. The humanitarian effort, in fact, was more involved with the Burundians, who had just had a coup d’état. Over 300,000 Burundians were on the southern border, and the humanitarian aid was going there, but the Rwandans, who were dying because of a drought and were not being fed, were killing the Burundians to get the food that the Burundians had been given by the international community because they had refugee status. So a lot of that nuancing could have happened if the political will and resources were there. It would have also been more cost effective.

In regards to classic warfare, there is no doubt that special forces have always existed and that there is always a lot of sloppy stuff. But in this circumstance, we were not trying to marry these big organizations with a known and easily identifiable enemy. Would we have been more successful if we had had support to advance the moderates in Rwanda to overturn the extremists? Yes, but there was nothing. But no one even wanted me to provide me with riot gear so that one group could have options between violence and doing nothing. I am not disagreeing with anything you say, but its just much more sophisticated. And people don’t like it because its ambiguous; it’s not neat, it’s complicated, and yes, you’ll take casualties.

The Americans got a bloody nose in Somalia. Yet there are 1.6 million people in uniform in the United States military. The Americans still packed it in, leaving the Pakistanis and the Canadians and others to handle the situation. I feel terrible about the September 11 terrorist attacks – it was absolutely grotesque - but you mobilized the world. No one was mobilized when 800,000 were killed in Rwanda, and they are just as human.

QUESTION: We had a discussion here not long ago with a realpolitik-er who answered no to my question about whether the U.S. had any self-interest in the Rwandan problem in 1994. What would you say to American political leaders back then who said we had no interest in Rwanda? What do you say about the realistic interests?

GEN. DALLAIRE: On the morning of April 7—and remember that on April 6th the presidential plane was shot down and the killing commenced—your ambassador to the United Nations said to the Security Council: “We will not get involved in Rwanda, and we will support no one who does.”

Many of these nations do not put our countries at risk. I mean Canada was not at risk with Rwanda. So the real question is: is the Western world prepared to spill blood for advancing human rights in far-off lands that mean nothing, except for one small fact: they are exactly the same as us. People are not different; the circumstances are different.

QUESTION: I used to think Rwanda was an aberration, but I soon learned that what happened in Rwanda was the result of a structural problem. You basically have a tension between what is in our hearts—to help the downtrodden and oppressed and others—and the international system, which is based entirely on national interest. You can come to the Carnegie Council on Ethics and International Affairs and discuss these issues, but if you go to the Security Council, ethics and international affairs is an oxymoron. Is it kinder to make the 80% of humanity that needs help to believe in the illusion that there is a world that will help them, or is it kinder for us to tell them there is no international safety net, that the UN system focuses purely on the short-term national interest?

GEN. DALLAIRE: Well, the first thing I want to say is that it’s not a time factor. If time was a factor for me, I’d be a pessimist. The optimism comes with the fact that humanity continues. We constantly fiddle and maneuver, and every now and again, we realize humanity isn’t just us. I believe the UN is critical to avoiding crises and managing crises. Whether we can move that 80% depends on our ability over the years.

I was a soldier in the 1960s. If somebody mentioned human rights back then, we’d call him a commie pinko. Today, we teach it. Today, we educate soldiers about human rights and provide medical support and other services to prisoners. So that is one reason why I am optimistic.

Fifty years from now, what should historians be writing about the United States, or Canada, where I am from? What is our vision? Our self-interest and the advancement of our nations? Yes. But there should also be a strategic focus on that higher plane called humanity. I don’t think we’re allowed to abdicate that responsibility.

JOANNE MYERS: Thank you very much for being with us.